When was the term invasive species first used? It could have been 1891, when an article in The Indian Forester noted, “As [purple loosestrife] can exist under different climatic conditions and is an invasive species, it has extended far beyond its original home.”

When was the term invasive species first used? It could have been 1891, when an article in The Indian Forester noted, “As [purple loosestrife] can exist under different climatic conditions and is an invasive species, it has extended far beyond its original home.”

Or has a much earlier usage been hiding in plain sight all along, disguised in the common names of a weed whose presence in our lawns and in sidewalk cracks we owe to the early settlers? In 1672, in New England Rarities Discovered, the English traveler John Josselyn listed “such Plants as have sprung up since the English Planted and kept Cattle in New-England.” On his list was “Plantain, which the Indians call English-Mans Foot, as though produced by their treading.” “English-Mans” or White Man’s Foot! Algonquians of the Eastern Woodlands, whose names no white recorded, had found a much more poetic way to express the concept of “invasive species”––in a heartbreakingly prescient way. The invaded, not the invaders, first defined the ecological issue.

In 1748, the Swedish botanist Peter Kalm reported from Philadelphia:

“The broad plantain, or Plantago major, grows on the high-roads, foot paths, meadows, and in

gardens in great quantity. Mr. Bartram had found this plant in many places on his travels, but he did not know whether it was an original American plant or whether the Europeans had brought it over. This doubt had its rise from the savages (who always had an extensive knowledge of the plants of the country) prentending that this plant never grew here before the arrival of the White Men. They therefore gave it a name which signified the (Englishman’s) foot, for they say that wherever a European had walked, this plant grew in his footsteps.”

By 1847, William Darlington, M.D., in his Agricultural Botany, observed,

“This foreigner is very generally naturalized; and is remarkable for accompanying civilized man, -growing along his footpaths and flourishing around his settlements. It is said our Aborigines call it “the white man’s foot,” from this circumstance. Perhaps the generic name (Plantago) may be expressive of a similar idea,–viz. Planta, the sole of the foot, and ago, to act, or exercise. It is rather a worthless weed,–but is not much inclined to spread, or be troublesome, on farm lands.”

In 1855, Longfellow mentioned White-man’s Foot in “Hiawatha”:

“Wheresoe’er they move, before them

Swarms the stinging fly, the Ahmo,

Swarms the bee, the honey-maker;

Wheresoe’er they tread, beneath them

Springs a flower unknown among us,

Springs the White-man’s Foot in blossom.”

Back in 1652 in The English Physitian, the English herbalist Nicholas Culpepper had written that plantain

“groweth so familiarly in meadows and fields and by pathways, and is so well known that it needeth no description. . . . The clarified juice drank for a few days helps excoriations or pains in the bowels. It stays all manner of fluxes, even women’s courses, when too abundant, and staunches the too free bleeding of wounds. It can also be profitably applied to all hot gouts, in the hands and feet. It is also good to apply to bones out of joint, to hinder inflammations, swellings and pains that presently rise thereon. Boiled in wine, it kills worms which breed in old and foul ulcers. One part of the herb water and two part of the brine of powdered beef, boiled together and clarified, is a remedy for all scabs and itch in the head and body, tetters, ringworms, shingles and running and fretting sores.”

So the introduction of plantain into North America was likely intentional: colonists doubtless considered it necessary medicine. But that’s only part of the story: each plant produces 20,000 tiny seeds, so every muddy sole, every snagged stocking, the hem of every skirt, the foot and coat of every domestic animal furthered its dispersal. In the ground, the seeds remain viable for at least 40 years. As the rapid spread of common plantain chased the westward expansion of the colonies, the Native Americans added it to their extensive herbal remedies. In addition to the familiar uses treat for wounds and as a topical application to ease skin irritation, they chewed it to ease the pain of toothache, gave it to young children to strengthen them, and brewed it into tea to treat diarrhea and other intestinal troubles. In 1870, in his New Family Herbal, Matthew Robinson mentioned an Indian who received a great reward from the Assembly of South Carolina for his discovery that Plantain was “the chief remedy for the cure of the rattlesnake.”

Darlington thought that the plantain was “not much inclined to spread,” but White Man’s Foot, following in the white man’s footsteps, has conquered the continent. Now classified as a weed everywhere, in places a noxious one, it was once so valued as an herbal remedy that it was grown in the garden. Buzzing not too faraway, perhaps, was what some called “the White Man’s Fly”: the familiar European honeybee.

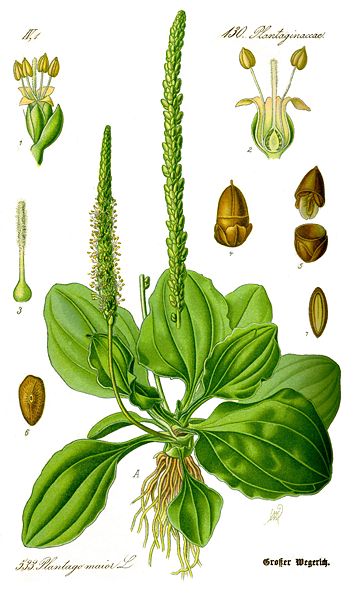

Common Plaintain

Plantago major

Native range: Europe and eastern and central Asia

Invasive range: All 50 states, Puerto Rico, Virgin Islands, Canada.

Habitat: Footpaths, roadsides, lawns, and waste areas.

Description: Oval leaves. Tiny greenish white flowers.

How to Prepare

Young leaves can be added to salads or cooked as greens.

As the leaves grow, they become stringy and tough and are better brewed as a tea. Flower stalks can be eaten raw, boiled, or sauteed.

There is some evidence that extracts from Plantago major may be effective in treating liver cancer.

{ 6 comments… read them below or add one }

I never knew this was edible! Like TheMule said, great for bee stings, but also for slivers. It pulls the sliver right out. I didn’t believe it at first, but I’ve never seen it fail since: rough up the surface of the leaves until they are wet, apply to the sliver and hold it there for several minutes. Either the sliver will be gone, or so far out of the skin that it can easily be removed by tweezers.

Thank you for the great identifying tools. I was looking for exactly this kind of info and have been to several sites and none were as thorough as yours.

There are two plantains that flourish in North America. The one you picture is native, the other Plantago lanceolata is the invasive. This one was used by Native Americans medicinally before the settlers came.

Thanks, Joan. We’ll look into this and update the image.

From my reading of the USDA site (http://plants.usda.gov/), both Plantago major and Plantago lanceolata are considered nonnative invaders in the U.S.

This plant had terrific anti-inflammatory properties. Mash up leaves and put on skin. Great for banged shins and bee stings.