Alliaria petiolata

Native range: Europe, Asia, Northwest Africa

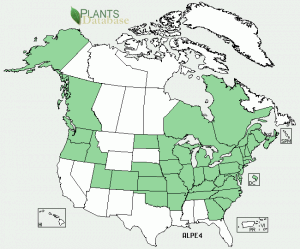

Invasive range: Much of the Lower 48, Alaska, and Canada. (See map.)

Habitat: Moist, shaded soil of floodplains, forests, roadsides, edges of woods, and forest openings. Often dominant in disturbed areas.

Description: Biennial herb. First-year plant has a rosette of green leaves close to the ground. Second-year flowering plants 2 to 3 feet in height with small white flowers. Four petals in the shape of a cross. Coarsely toothed leaves have odor of garlic when crushed.

Impacts: Spreads rapidly on forest edges and understory, where it can crowd out native wildflowers and tree seedlings. Overbrowsing by deer herds can increase risk to native ecosystems.

Garlic mustard is a Eurasian native likely introduced to North America by early European colonists as a food and medicinal plant—which then hopped the garden fence and went wild. In 1868, it was recorded “outside cultivation” on Long Island, flourishing in what field guides call “disturbed ground”: the edges of roads, railroads, trails, fields, and abandoned lots. From there, like most invaders, once it establishes in a new location, it invades undisturbed plant communities and becomes the dominant species. The insects that feed on it in the Old World aren’t present in the New. Because white-tailed deer rarely feed on garlic mustard, they may encourage it by consuming native plants instead, and their trampling as they browse disturbs the soil, encouraging invasive seeds—which can germinate up to five years after being produced—to grow. Its roots inhibit the growth of some below-ground fungi that many native plants require, reducing the ability of tree seedlings to survive in a sea of garlic mustard. Somewhat surprisingly, researchers have found that invaded areas have a greater diversity of fungi, perhaps because the dominant ones disappeared.

Garlic mustard has headed west from the northeastern coast, taking the eastern and midwestern US, crossing into Canada, mounting incursions into western states, including the Pacific Northwest. Reproduction is entirely by seed, and each plant produces about 350 seeds, which means about 100,000 seeds per square foot. Its spread in the East has been exponential, nearly 4000 sq mi per year, making it the dominant under-story species in woodland and flood-plain habitats, where eradication is most difficult.

Garlic mustard has headed west from the northeastern coast, taking the eastern and midwestern US, crossing into Canada, mounting incursions into western states, including the Pacific Northwest. Reproduction is entirely by seed, and each plant produces about 350 seeds, which means about 100,000 seeds per square foot. Its spread in the East has been exponential, nearly 4000 sq mi per year, making it the dominant under-story species in woodland and flood-plain habitats, where eradication is most difficult.

The plant spends its first year as a rosette, then bolts in early spring of its second year, sending up a stalk over 3′ tall, so it’s hard to miss. Leaves are dark green, coarsely toothed, and deeply veined. All parts of the plant smell like garlic, though less so towards fall. The basal rosettes stay green all year, even under snow.

We’re the only ones who will eat it—even white-tailed deer won’t touch it—so forage away, as long as you’re at least 1/4 mile from the side of a busy road. Avoid plants that may have been treated with weed killer or other pollutants. Make sure there’s no poison ivy growing in with the garlic mustard. Make sure you have the right plant—the rough-toothed leaves and garlic odor when crushed are giveaways—then pull it up by the roots. Don’t scatter any seed as you bag up the whole thing. The roots will keep it fresh until you’re ready to cook. Then cut off the leaves, and discard the stalk and roots in a sealed bag for disposal. Do not plant or compost!

Wash the leaves. Young plants, with their mild mustard-garlic flavor, can be used raw in salads. Cooked, the flavor’s even more subtle. Older leaves, fresh or dried, come through stronger, tending toward bitter, and are great in soups, marinades and dry rubs, especially with meat. If the plant is in full flower or has produced seeds, it will be more bitter.

Ava Chin, urban forager at the New York Times, recently reported on her success with garlic mustard pesto:

“Back in my kitchen, I cleaned the garlic mustard by soaking the leaves in a bowl of water before drying them off. I then blended them in a food processor with extra virgin olive oil, walnuts, salt and pepper, and a teaspoon of apple vinegar. That evening, we had a wild-tasting seasonal pesto pasta with shaved Parmesan that even our toddler enjoyed.”

Harvest

According to Russ Cohen of the Massachusetts Department of Fish and Game, “The most palatable parts of the garlic mustard plant, which do not require parboiling, are the tender portions of developing stems of second-year plants when they’re less than a foot tall and before the flower buds form.” In the Northeast, the plants are typically at this stage at the end of April into early May. “The stem is relatively mild and tender enough to be eaten raw,” Cohen writes, “and also lends itself well to a quick stir-fry or a chopped-up ingredient in soups.”

Wildman Steve Brill, a New York City forager, notes that the root of young basal rosettes (bottom left) tastes like horseradish and the seeds, which can be gathered from dead plants in the summer, are fantastic for anyone who likes spicy foods.

Of the seasons of garlic mustard, Josey Schanen writes on our Facebook page: “Eat the sprouts in early to mid spring, the basal leaves and roots in late fall and early spring, the stalks and stalk leaves in mid-late spring, and the seeds from mid summer and mid fall.”

To safely, and most effectively, harvest garlic mustard, remove as much of the plant as possible, including the root, before it goes to seed. If it has seeds, be careful not to disperse, as they can remain viable for years. Don’t compost garlic mustard—burn or bag and discard the unused parts.

Recipes

Garlic Mustard Pesto

Wildman Steve Brill has served this pesto on his tours of Central Park in New York. He told us we could post it, with a link to his website.

4 cloves of garlic

3 tablespoons garlic mustard taproots

3/4 cups parsley

1 cup garlic mustard leaves

1 cup basil

2 cups walnuts or pine nuts

1/2 cup mellow miso

1 1/4 cup olive oil or as needed

Chop the garlic and garlic mustard roots in a food processor.

Add the parsley, garlic, garlic mustard and basil and chop.

Add the nuts and chop coarsely.

Add the olive oil and miso and process until you’ve created a coarse paste.

Makes 4 cups

Garlic Mustard Cocktail

Mike Ryan, head bartender, Sable Kitchen & Bar

1 oz Brugal white rum

3/4 oz blanco tequila

1/2 oz creme de moutard*

2 dashes orange bitters

3 garlic mustard leaves, muddled

*Creme de Moutard:

1 cup garlic mustard leaves, cleaned

1 cup pure grain alcohol

1 cup garlic mustard roots, cleaned and chopped

1 cup water

1 cup granulated sugar

Place 1 cup garlic mustard leaves in 1 cup grain alcohol. Let sit 18 hrs. Strain and set aside.

Cover chopped garlic mustard roots with 1 cup water and bring slowly to simmer but do not boil. Add 1 cup granulated sugar and stir to combine. Let cool 1 hour and strain.

Combine alcohol infusion with 1 1/4 cup of the syrup. Let sit overnight to allow flavors to marry.

Stir. Strain. Serve garnished with floating garlic mustard leaf.

Black Bass with Burdock and Garlic Mustard

Jean-Georges Vongerichten, Food & Wine, April 1997

3 tablespoon canola oil

3/4 lb burdock root, peeled and sliced crosswise 1/8 inch thick

1 medium shallot, minced

1 large garlic clove, minced

1 tablespoon soy sauce

4 6-oz black bass fillets

Salt

Cayenne pepper

3 tablespoon unsalted butter

1 lb garlic mustard greens, tough stems removed, leaves finely shredded

In medium nonreactive skillet, heat 2 tablespoons oil. Add burdock, shallot and garlic; cook over moderate heat, stirring often, until burdock is golden and barely tender, about 15 min. Add 6 tablespoons water, 1 at a time, cooking until nearly absorbed between additions. Add soy sauce, and remove from heat. Cover and keep warm.

Make 3 small slashes about 2″ long and 1/8″ deep in skin side of the fillets. Season both sides with salt and cayenne.

In large nonstick skillet, heat remaining 1 tablespoons oil. Add the fish, skin side down, and cook over high heat until opaque around edges, about 6 min. Gently turn and cook for 1 min.

While the fillets are cooking, in medium saucepan, melt butter over moderate heat. Swirl in 3 tablespoons water, 1 tablespoon at a time. Add Garlic mustard greens and cook, stirring, until just wilted, about 1 minute.

Spoon burdock mixture onto 4 plates and top with piece of fish, skin side up. Spoon greens around fish and serve.

{ 4 comments… read them below or add one }

The standard method of decreasing bitterness in a salad is to increase the proportion of the acid source (lemon juice, vinegar) in a vinaigrette. That is, instead of the typical 1:3 acid:oil ratio, change it to 1:1. Adding some of your favorite sweetener (brown sugar, honey, or artificial sweetener) will also mellow the bitterness – think of raspberry vinaigrette. You might want to treat the salad with the vinaigrette about 15 minutes before eating to allow the acid to do its thing (you must make sure there’s no salt in your vinaigrette to prevent the leaves from wilting.)

Note: these leaves are not super-bitter. If you can tolerate a mass-produced light beer, you can tolerate these leaves.

If poison ivy is growing in the area can you still forage and wash plant to rid the poison ivy? Or best to not forage at all?

Do you have any preparation tricks to decrease bitterness?

I greatly enjoyed reading this article. Here’s some additional info:

Unlike most wild greens, it’s the leaves from the stem of the 2nd year plant, when it’s flowering, that are the best. In its first year, the young basal (bottom) leaves are somewhat bitter, although they’re superb in pesto, and you can attenuate the bitterness by combining them with parboiled lesser celandine, which counterbalances garlic mustard’s intensity perfectly.

To learn more about wild foods and my foraging tours (which take place throughout Greater NY), check out my site or download my iOS/Android app, Wild Edibles.

{ 4 trackbacks }